In 2021, I watched 508 movies. This is not healthy or wise behavior, but this was not a healthy or wise year. In order to extract at least some value out of those 1000ish hours, I’m going to write about it.

I watched 50 Japanese films in 2021, but I admittedly could have cast a wider net. 49/50 were either samurai or crime films, and many were both.

Of course, both those genres have an awful lot of room for variance. I saw samurai films that were vicious, bleak, and humorless, and others that were more-or-less comedies where people carried swords around. One crime film might chronicle a blood-soaked war between two rival yakuza factions, while another might be a suburban wife’s quietly desperate quest to find her missing husband.

I overdid it, sure, but I was rarely bored, and almost everything I saw from Japan had something unique going for it.

…ok, admittedly, a few of the Zatoichi and Red Peony Gambler sequels might have wanted a little for unique. I probably won’t be talking too much about those.

That feels like plenty of preamble, so without any further adieu, let’s get into it. The first few sections cover some thoughts on my most-seen Japanese actors, actresses, and directors for the year, but if you’re just interested in the movies themselves you have my authorial permission to skim or skip ahead.

MOST WATCHED ACTORS

7 MOVIES: Jō Shishido

The Dragon of Macao; Cat Girls Gamblers: Abandoned Fangs of Triumph; Velvet Hustler; Blood for Blood; The Most Terrible Time In My Life; Stairway to the Distant Past; The Trap

It’s no secret that Jō is my favorite Japanese actor. I covered him fairly extensively for Noir City Magazine in 2020, and my affection for his work has only grown since. The crop of his pictures I saw in 2021 weren’t his best—the downside of loving an actor too much is that you eventually run out of those—but every one of them had plenty to recommend it (Jō’s performance often topping that list ). Velvet Hustler and Dragon of Macao are the kind of jazzy Nikkatsu crime thrillers he made his bones on, both letting him ham it up in charismatic villain roles. Blood for Blood echoes his other collaborations with director Yasuharu Hasebe, an extremely violent but surprisingly tenderhearted revenge opera. He appears as a mysterious antihero in the best of the three Cat Girls Gamblers films, and it’s a real shame they never made the fourth film its ending suggested was coming given how well he fit into that world. Finally, he riffed on his own image as sort of a P.I. Gandalf or Obi-Wan figure in the three Maiku Hama pictures (The Most Terrible Time in My Life, Stairway to the Distant Past, The Trap), serving as a genre-wizened mentor to Masatoshi Nagase, lending some winking gravitas and credibility to the proceedings. While only one of these seven films saw Jō in the central role (Blood for Blood), they all gave him something worthwhile to do, and they’re all worth a watch for anyone who loves him like I do.

8 MOVIES: Tomisaburō Wakayama

The Tale of Zatoichi Continues; Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword; Okatsu: The Female Demon; Red Peony Gambler; Red Peony Gambler: Gambler's Obligation; Quick-draw Okatsu; Red Peony Gambler: Flower Cards Game; Sympathy for the Underdog

Most famous for the Lone Wolf & Cub series of samurai epics, my exposure to Wakayama came primarily from two other long-running jidaigeki series: Zatoichi (opposite his real-life brother in the title role) and Red Peony Gambler. The Zatoichi appearances utilize his swaggering menace as two very different kinds of foe for the blind swordsman, and they stand out as two of the best in the series. Red Peony, meanwhile, subverts Wakayama’s badass reputation and present him as a bumbling, childlike yakuza initially dependent on the skills of the titular gambler (though the third movie begins to build him up as a legitimate power in his own right). He also features in two of the three Okatsu pictures, first as one of the main antagonists in Then Female Demon and then as an imposing bounty hunter of flexible allegiance in Quick-draw Okatsu, in which he steals every scene he’s in. He has a similarly conflicted—and similarly compelling—turn in Sympathy for the Underdog as a principled, one-armed yakuza boss dragged reluctantly into a larger conflict between two other families. While none of these performances give him the same shine as a starring vehicle like Lone Wolf, they do showcase a game and gifted character actor hiding within the big marquee star.

11 MOVIES: Shintarō Katsu

The Tale of Zatoichi; The Tale of Zatoichi Continues; New Tale of Zatoichi; Zatoichi the Fugitive; Zatochi on the Road; Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold; Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword; Fight, Zatoichi, Fight; Adventures of Zatoichi; Zatoichi’s Revenge, Zatoichi and the Doomed Man

A unique entry for me to write here, as normally I try to race through all the different characters and performances for an actor…but in this case, all eleven movies are one character, and one performance. That volume speaks to just how enduring and effective Katsu’s portrayal of Zatoichi is. He’s such a unique action hero, too. While James Bond, Indiana Jones, Zorro, and countless other pulp franchise heroes are cool, collected, and confident. Zatoichi is socially clumsy, self-loathing, awkward, and occasionally even oafish. Sometimes those flaws play as obfuscation, other times they play sincere; it’s a credit to Katsu’s work that both interpretations feel authentic every time, and that Zatoichi himself remains endearing and compelling throughout the series. It’s a demonstrably immortal performance—he gave it twenty-six times in the cinema, and another hundred or so on TV—and one that works in direct contravention of traditional masculine hero archetypes. Irreplaceable.

MOST WATCHED ACTRESSES

4 MOVIES: Junko Miyazono

Okatsu: The Female Demon; Okatsu the Fugitive; Quick-Draw Okatsu; Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams

Three of the four films in which I saw Junko Miyazono this year saw her playing a vengeful woman-done-wrong named Okatsu, but they are three different Okatsus. It’s a strange anthology series with no continuity but one constant: don’t piss off Junko. The first—The Female Demon—is the best of the trilogy, a vicious, cynical, feminist—and even queer!—riff on The Count of Monte Cristo. Miyazono’s ability to portray vulnerability both sincere and manufactured, and to rapidly wield the latter as the hidden knife Okatsu intends it as, is the lynchpin to the picture. The sequels suffer some both due to weaker scripts, and on account of making Okatsu more of a traditional action heroine. The first Okatsu is deadly (and compelling) because of her wits and her will, the second and third rely more on their swordsmanship, and sadly that’s much less interesting. The one non-Okatsu film I saw her in was less interesting even than that, a trashy exploitation film called Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams. Miyazono brings some energy and nuance in her scenes, but there aren’t enough of them to salvage the picture.

5 MOVIES: Ikuko Môri

The Tale of Zatoichi; Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword; Fight, Zatoichi, Fight; Adventures of Zatoichi; Lefty Fencer

Ikuko Môri was in four of the eleven Zatoichi films I saw, including the first. Usually, she’s a fun value add in a bit supporting role (and she has a similarly small role in the excellent Lefty Fencer as well)… but then there’s Fight, Zatoichi, Fight, which gives her center stage. “Zatoichi and the romance that can never be” is a trope the series goes to in almost every film, but this—along with original love interest Otane and her doppelganger in the 11th picture—is one of the best executions of it. Môri plays a spunky pickpocket prostitute who is hired by Zatoichi to help care for an infant he’s found himself saddled with, and as they travel together she comes to see a path towards redemption—and even happiness—in Ichi, but can’t figure out how to make the blind man see the same thing. Heartbreaking stuff, perfectly played by Môri, and one of the narrative high points of a series that isn’t always known for its character work.

5 MOVIES: Meiko Kaji

Melody of Rebellion; Blood For Blood; Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion; Wandering Ginza Butterfly: She-Cat Gambler; Lady Snowblood

Meiko Kaji is my no-brainer pick for the greatest female action star of all time, though she only especially shows off why in two of these five films. Lady Snowblood is the most well-known, a blood-drenched tale of samurai revenge with an errant poetic streak. She-Cat Gambler is less heralded, but still a ton of fun. Blood for Blood and Melody of Rebellion both also have some pretty decent action in them, but Kaji is unfortunately confined to girlfriend duty and misses the bloodshed. Of the two, Blood for Blood is the better film, but neither is really one I’d point to as a Meiko Kaji vehicle. Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion, though, certainly is, a grindhouse/arthouse hybrid epic of surreal feminist vengeance. These films aren’t all essential Kaji—though Snowblood and 701 certainly are—but they’re a nice snapshot of her range, from the cocky, charming gambler of Ginza Butterfly, to the driven anti-heroine of Lady Snowblood, to the pathologically implacable living vendetta of Female Prisoner to the vulnerable, wounded yet warm nurturer of Blood for Blood to the spunky, out-of-her-depth love interest of Melody of Rebellion. Kaji is one of the greatest killers in cinema—and she’s certainly got its greatest death glare—but that was far from the only tool in her kit.

OTHER STANDOUT ACTORS & ACTRESSES WORTH MENTIONING:

Toshiro Mifune, Tatsuya Fuji, Yumiko Nogawa, Masayo Banri, Kō Nishimura, Eiji Gō, Saburo Date, Akaji Maro, Gen Kimura, Reiko Ike

MOST WATCHED DIRECTORS

3 MOVIES: Harayasu Noguchi

Cat Girls Gamblers; Cat Girls Gamblers: Naked Flesh Paid Into the Pot; Cat Girls Gamblers: Abandoned Fangs of Triumph

The Cat Girls Gamblers series from Harayasu Noguchi is somewhat misleadlingly titled—there’s mostly just the one girl gambler, and she’s not especially cat-like—but it does what it does quite well. It could easily have been a trashy exploitation series, but Noguchi takes a higher road full of thoughtful, elaborate cinematography and mise en scene backed by character-first storytelling. While the films lack a credible villain, it’s a legitimate pleasure to watch Yumiko Nogawa’s Yukiko grow from feisty in-over-her-head novice in the first film to hardened, badass swordswoman by the last, and the addition of Jō Shishido’s mysterious, allegiance-agnostic drifter further ups the stakes and entertainment value in the series’ final installment. It’s disappointing we never got the fourth movie set up by its ending, which had set the stage for further adventures for the franchise’s two strongest characters beyond its usual setting and structure.

3 MOVIES: Kimiyoshi Yasuda

Zatoichi on the Road; Adventures of Zatoichi; Lefty Fencer

Kimiyoshi Yasuda made two of the weaker Zatoichi pictures, then went off to make a movie about a different disabled samurai. That film—Lefty Fencer—could give even the best Zatoichi pictures a run for their money, never mind Yasuda’s. There’s a thousand ways his approach to Lady Saizen, the one-armed, one-eyes samurai heroine of Lefty Fencer differs from his take on Ichi, and it’s fair to question why he’s such a good fit for her and a relatively lackluster fit for the more famous hero given their superficial similarities. I think it comes down to viciousness. Since the very first Zatoichi film by Kenji Misumi, the series tend to run best at a slow pace, with violence as a reluctant last resort for the warm-hearted title character. I think Yasuda understands that, knows it goes against his instinct, and leans too far into it as an over-correction. His Zatoichi movies are among the most ponderous, and often feel stuck in the mud. Lefty Fencer, by contrast, stars a woman who believes that the best way to avoid violence is to initiate it; if Ichi drawing his sword is a reluctant goodbye after all else fails, Saizen drawing hers is an aggressive handshake as soon as she walks into the room. This leads to a meaner, more kinetic movie that’s all killer, no filler, and lets Yasuda do what he does well, instead of forcing him to fumble in the direction of what Kenji Misumi does instead.

4 MOVIES: Kaizo Hayashi

The Most Terrible Time In My Life; Stairway to the Distant Past; The Trap; Cat’s Eye

I never cared much for Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer—the most over-the-top violent and misogynistic of classic noir’s seminal heroes—but Kaizo Hayashi’s trilogy reimagining him for Japan (Maiku Hama or Mike Yokohama depending on the movie) makes the character infinitely more appealing. Instead of playing Hama straight as a hard-boiled mega-tough, Hayashi understands that the character is inherently ridiculous, and leans into it. Where Spillane’s Hammer bullies the world around him into submission, Hama is an upbeat, somewhat goofy soul regularly shocked and overwhelmed by the sheer darkness and evil around him. He’s no pushover—though he can seem like one at first—and can fight back with just as much bitterness and angst as his American namesake, but there’s a lot more pathos to it when him going to that dark place is a desperate response to external darkness, instead of inhabiting one as his natural state. Hayashi surrounds this more human Hama with a deep bench of memorable supporting players and antagonists, and shoots it with almost Seijun Suzuki-esque pop lunacy, energy, and artistry. In the Hama pictures, he’s got enough control over that roiling creative madness to turn in some really excellent detective pictures. In Cat’s Eye, it overwhelms him, producing a gloriously camp but not especially comprehensible spasm of a superhero movie. But three out of four times I saw his work, he hit the nail on the head. I guess the trick was in finding the right Hammer.

BOTTOM OF THE BARREL

The worst Japanese movies I saw this year were more mediocre or forgettable than truly bad… with one exception.

Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams (2001)

There are some truly great Japanese exploitation films out there that rise above the genre’s baser impulses or defy its more problematic conventions to provide artistic, meaningful cinema. This is not one of them.

OLD FAVORITES REVISITED

Anything I’ve seen before isn’t eligible for the Top 10, but on the other hand if I watch a movie I’ve already seen, it’s likely because it’s excellent. I re-watched six Japanese films this year, all of them good, but these five were the best.

Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion (1972)

Meiko Kaji’s Scorpion stalks her prey, fittingly accompanied by one of the truly great cinematic musical stings.

Now this is one of those Japanese exploitation films that rises above the genre. The story is an old one: a woman is done incredibly wrong by her corrupt cop boyfriend, and is locked away in an abusive prison. She tries repeatedly to escape that she might track him down and do him worse. It’s a familiar setup for a women in prison movie, but part of what differentiates 701 is the way it makes sure its protagonist is always the center of power. Even with her hands and feet bound on the floor of a jail cell (punishment for her latest escape attempt), she’s a threat (and the vicious shrew preparing her gruel learns that lesson the hard way). While there’s no shortage of degradation she’s put through by warden and inmates alike, it all feels not like titillation or excess but like desperate grasping for power on their part; their efforts quickly become more about convincing themselves she can be broken than actually breaking her. She can’t, and what her tormentors fail to realize is that the more desperate they become, the more likely they are to leave an opening, to make a mistake… and that’s when she strikes. Like a scorpion. It’s that patience and perseverance that make her so unique in the annals of revenge; in most blood-soaked revenge films, the hero or heroine is a deadly physical threat, skilled with knives or guns or martial arts. Nami Matsushida isn’t—when she finally gets her hand on a knife, there’s little grace or skill to the way she uses it, more slasher than samurai—but she’s patient and implacable, unraveling her enemies psychologically until they’re so blinded by rage or fear they leave themselves open physically. Combine that unique hook with a pantheon-level performance from Meiko Kaji and surreal, pop-art direction from Shunya Itō, and what you have isn’t so much an exploitation film as it is a phantasmal revenge epic in disguise. After all, expecting a camouflaged scorpion to be what it purports to is the easiest way to get stung. Female Prisoner 701 stings in a way that lingers.

Lady Snowblood (1973)

Meiko Kaji’s bloody lady samurai strolls through the snow, keeping the title honest.

Of course, Meiko Kaji could also do the more traditional revenge heroine, too. Toshiya Fujita’s Lady Snowblood is the great samurai vengeance epic, a blood drenched poem of vendetta. Here Kaji is pursuing a grudge she was born to, fulfilling the spiteful dying wish of her mother. The movie is more thoughtful than it needs to be about that, and about vengeance in general… but it’s also brutally effective, with dazzling action set-pieces and hateful intensity. It’s a credit to Kaji that she could take two such imposing and imperious characters with identical goals and make them feel wholly different. Her character here is more thoughtful, more empathetic, and less surefooted; she has needs—or at least wants—beyond revenge, and while she can’t bring herself to prioritize them their very presence brings a wistfulness and sadness to her quest that isn’t present in the more single-minded 701. Lady Snowblood also has a bit more on its mind thematically, going beyond meditations on revenge into questions of nationalism, duty, and self-determinism… in between all the swordfights, moral quandaries, and stunning cinematography.

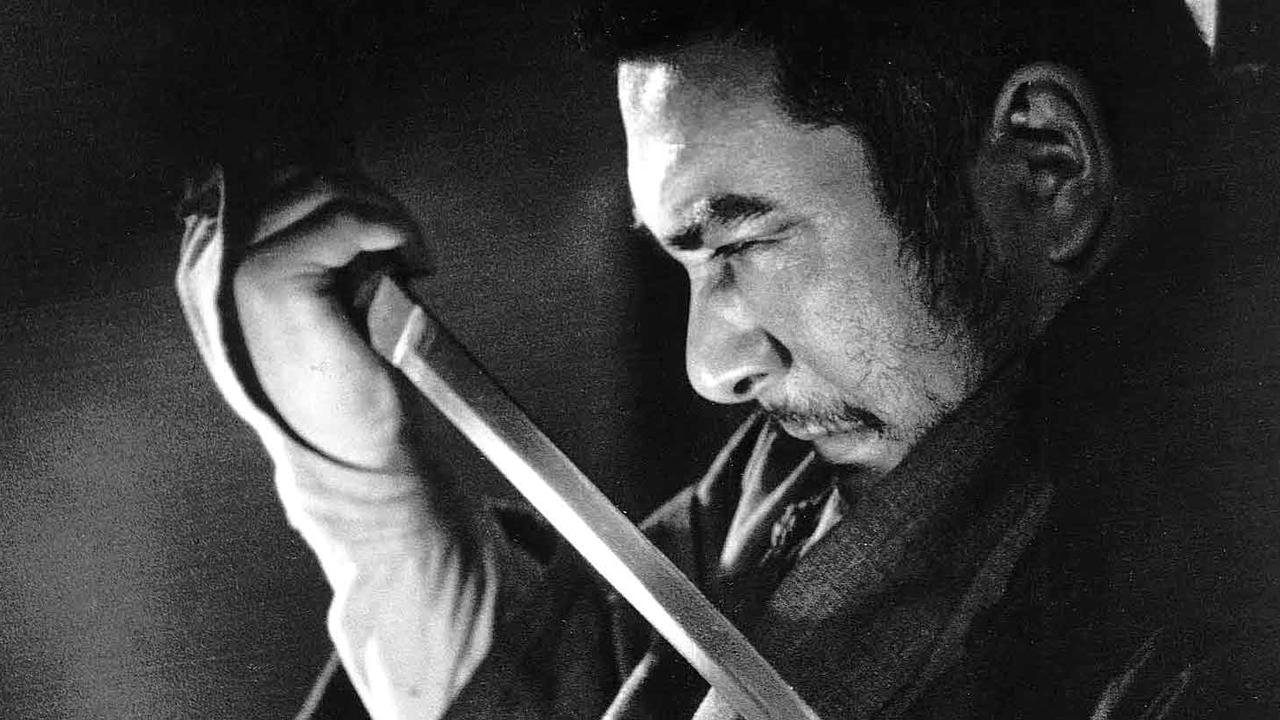

Yojimbo (1961)

Toshiro Mifune does some thinking, which is generally bad news for bad guys.

I first saw Yojimbo over fifteen years ago, but it’s lost none of its power. It’s a simple enough story— Toshiro Mifune’s wandering samurai comes across a town locked in a battle between two rival gangs, and sees an opportunity to make some money, or at least have a few laughs, pitting them against each other. It’s bleaker than you remember—one of the only sympathetic characters in the movie besides Mifune is the town’s coffin-maker—but with that bleakness comes excellent, understated gallows humor, and surprising moments of catharsis. Mifune is perfect throughout, pleasantly amused by his own cleverness and the villains’ lack thereof, and yet never wholly lets his guard down; his confidence and his caution come from the same place: experience. He’s a character that tells us so much about where he’s been and what he’s done without ever saying a word about it. It’s such a perfect film that it’s easy to see why it’s so often been remade or imitated; most famously by A Fistful of Dollars but most successfully, in my opinion, by Youth of the Beast, which understood that the original could not be directly improved upon but could serve as an excellent template for a different kind of movie. Fistful feels like the karaoke version—all the same beats, just with a different accent—while Youth feels like an out-of-genre cover, taking the core of the structure but playing new notes around it. It’s a testament to Yojimbo’s power that even the karaoke and cover versions of it are all-timers.

The Tale of Zatoichi (1962)

Shintarō Katsu’s blind yakuza prepares to help some (short)sighted men see the error of their ways.

There’s an easy comparison to make between Zatoichi and James Bond; both debuted on-screen in 1962, launching franchises that endure to this day with over twenty-five cinematic installments. As characters, they’re not much similar in temperament, motivation, methodology, or much else… though they do share a passion for gambling and a truly staggering proficiency in the violent arts. The main commonality for me, though, is the way they both arrived so fully formed in their very first movie. Sean Connery was famously so striking, and so good, in Dr. No that Ian Fleming re-wrote the literary version to be more like his portrayal. For Zatoichi, Shintarō Katsu’s so good his first time out that he kept running back the performance for twenty-five more movies (and a hundred episodes of television). I’ve only seen twelve of those one-hundred and twenty-six outings as the character, but it doesn’t seem like he ever needed to add anything; he got it so right on the first try even he couldn’t improve upon it. Some of the later movies have better villains, or better fights, but none have a better central performance. I think that’s partly because that first movie had such a perfect story built around him, that let Katsu explore the most interesting parts of Ichi. His sentimentality and his sadness are so much more integral to the character than his swordsmanship, and his doomed friendship with a fellow fisherman and star-crossed love that never was with Otane are the perfect tragic snapshots of both what makes him a good man, and what keeps him a lonely one. Otane is the first and greatest of many Zatoichi love interests who just can’t seem to convince him he deserves the happiness she’s desperate to give him, riffing on the central irony that blind Ichi can see things much more clearly than most sighted men, while Otane sees Ichi better than he sees himself. For a sword fighting movie, this first Zatoichi isn’t very action packed; thanks to Katsu’s perfect portrayal and the strong character work and story structure around him, it still feels like it is. That elemental command of an audience’s attention is the other thing he shares with Connery’s Bond…. though of course Ichi commanded it for longer.

Wandering Ginza Butterfly: She-Cat Gambler (1972)

The guys in the suits think they have Meiko Kaji and Sonny Chiba outgunned. God help them.

She-Cat Gambler is the second Wandering Ginza Butterfly movie, though it’s nearly as much remake as sequel. In both, Meiko Kaji plays a friendly, confident gambler who stumbles into small-town yakuza nonsense, tries really hard to find a peaceful and equitable solution for everyone involved, then murders the everloving shit out of dozens of bad guys when they don’t let her. The second movie figured that the only thing that could improve on that formula was the addition of Sonny Chiba. If you’re only going to make one change, that’s not a bad one to go with. She-Cat Gambler isn’t quite the timeless masterpiece of 701 or Snowblood but it’s still an excellent action film, with two winning central performances, a brisk pace, and a glorious two-against-the-world murderparty of a finale. It shares something else besides Kaji with 701 and Snowblood (and, for that matter, Blind Woman’s Curse), namely that Quentin Tarantino steals shots and setups pretty liberally from all of them in Kill Bill. Watch enough Meiko Kaji, and that film starts to feel more and more like a clipshow. I mention this because even though She-Cat Gambler commits an even more obvious version of the same theft (stealing its entire plot from the first Wandering Ginza), it somehow feels fresher, even with thirty extra years on the shelf. I think it’s because Kaji is so good—and so good with Chiba specifically—that being a low-budget, borderline plagiaristic retread is kind of incidental instead of fatal. It’s a relentlessly fun movie that doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel, confident that it’s already got the best wheels in town. When your movie is running on the star power of Lady Snowblood and The Street Fighter* at the peak of their prowess, I guess it’s pretty hard to argue that you need to change the tires, no matter how well-worn.

*Never you mind that She-Cat Gambler predates both those roles. Kaji and Chiba were/are/will always be undeniable.

THE TOP 10

#10: Sympathy for the Underdog (1971)

In contrast to the careful restraint of his Battles Without Honor or Humanity series, Kinji Fukasaku’s Sympathy for the Underdog feels like Fukasaku trying to make a Yasuharu Hasebe movie, and the result is gangbusters. It’s a pretty boilerplate story—lifer yakuza gets out of jail after being betrayed, decides to go to Okinawa to rebuild his gang, comes into conflict with both his old organization and the local Okinawan gangs—but the execution is so slick and fun it all ends up feeling brave and wild. Like Hasebe, Fukasaku understands that the most interesting thing about yakuza hoods isn’t their toughness or killing power, but the quiet bonds between them. There are soft scenes between our main gangster and a woman who reminds him of his old flame that wouldn’t be out of place in a Wong Kar-wai or Mike Nichols picture, and there are dozens of little moments of masculine tenderness both between the members of the protagonist’s gang and the local Okinawans. We care more than we’d think about, say, Tomisaburō Wakayama’s gigantic, scarred, backflipping, one-armed Okinawan crimelord than we might expect based on that description (or, at least, care in a less comic-booky register), because the movie takes the time to show us his disappointed relationship with his idiot brother and his wounded sense of old-school honor…. and that’s really the whole movie in a nutshell: larger than life, hyper-violent spectacle painted over real emotion and ideas, all backed by a jazzy, melancholic score that keeps the tempo and the tone perfectly on-beat.

#9: Okatsu: The Female Demon (1968)

Junko Miyazono helpfully demonstrates the concept of irony for one of her captors.

Don’t Fuck With Junko Miyazono: The Movie. Okatsu is about as good a revenge movie as you could hope for, with an interesting, sympathetic protagonist put through the ringer, and in turn cultivating interesting, inventive revenge against those who wronged her. She’s ahead of her time, both as a vindictive, deadly woman the audience is actively encouraged to root for, and as a queer(ish) protagonist at a time when there really weren’t many, and certainly not in these kind of movies. How queer, exactly, is left somewhat to the audience’s interpretation; is she actually bi, or does she just pretend at it as a means to her ultimate revenge? It’s certainly not great that the villain’s lesbianism is presented in such a predatory fashion, but it’s not framed as purely evil, either. There’s real warmth in their scenes together, even if it’s at least partially manufactured on Okatsu’s side. Either way, it’s another brave choice in a movie that’s full of them. Another creative choice I quite like is that Okatsu doesn’t start as a naive, innocent waif like so many other female revenge heroines, but as a cunning, thieving grifter. She brings her grifter’s cunning to bear manipulating every one of her many foes. Where 701’s weapon is her will and Snowblood’s is her blade, Okatsu’s go-to is her empathy; she can quickly read what someone wants, and work it to her advantage. In that way she’s almost like Tom Ripley or Hannibal Lecter, only with Okatsu we don’t have to feel guilty rooting for her. She’s a perfect anti-hero, sadistic yet sympathetic, reaping righteous vengeance against people who are even worse than she is.

Beautifully shot, featuring a fascinating protagonist played with the intensity of an exposed nerve by Miyazono, Okatsu: The Female Demon is an exceptional revenge movie.

#8: Velvet Hustler (1967)

Tetsuya Watari gets his groove on.

Tesuya Watari has made a lot of forgettably competent crime movies—most notably his Outlaw VIP series—but this isn’t one of them. Velvet Hustler is so suffuse with style and charm, I’m shocked it isn’t more well-known (like Watari’s best/most famous film, Seijun Suzuki’s Tokyo Drifter). True, Velvet Hustler doesn’t have the iconoclastic fervor of a Suzuki picture, but it’s just as weird and fun in its own offbeat way. Watari plays a hitman who’s less interested in both the murders he’s involved in than the girlfriend of a man he’s accused of killing or the jazzy nightlife available to him between jobs. We’ve seen a thousand movies about dour, tortured, or taciturn hitmen, but relatively few about goofy, hedonistic ones (though Suzuki again bears mentioning for Branded to Kill). Not that melodrama isn’t regularly trying to horn in on his good time, particularly in scenes he shares with the detective trying to bust him. In another movie, those sequences would played as tense confrontations or slick showcases for the hitman’s superior cleverness, but in this one Watari can barely contain his impish smirk, and invariably blows off the detective mid-interrogation to return to a date or a drink.

Watari’s Goro is fun and charming in a breezy way these characters rarely are, and he’s complimented perfectly by Jō Shishido’s unhurried malevolence in the villain part. But there’s a fatalism to Goro that puts tragedy under the charm, as in a terrifically off-the-wall monologue in which he discusses the topless death of an old flame, pisses on the idea of a happy afterlife (including confidently asserting he’s headed to Hell himself), and somehow finishes up by telling a woman that she’s better off now that her beau is dead and that she should probably sleep with Goro about it. It’s an incredibly funny scene—and one that very few actors could pull off without it descending too far into farce—but it also speaks to the darkness under all of Goro’s flippant charisma.

That marriage of abject darkness and madcap good vibes pervades; the climactic confrontation with Shishido briefly devolves into a pillow fight, for instance, and Goro’s final scene would be the film’s darkest…if only it weren’t so damn charming.

#7: LeftY Fencer (1969)

Michiyo Ookusu reflects on the latest man dumb enough to fuck around in her presence, and her subsequent assistance in helping him find out.

“The clouds are gathering. Are you inviting the rain, Drenched Swallow?” Lady Sazen asks her sword in her first lines of the movie, brandishing it in front of a gang of crooks who’d been chasing a woman. She grins, “Drenched Swallow wants the rain of blood… Yasu, take care of the lady.” Yasu goes to usher the woman to safety, the men charge, and Sazen bites the sheath off Drenched Swallow and cuts them down.

It’s the sort of boastful confidence and blood thirst we’re used to seeing from our masculine samurai heroes, but less so from the women. Even Lady Snowblood, Red Peony, Crimson Bat, Ginza Butterfly, and Okatsu are fairly polite and demure, despite their murderous faculty. Lady Sazen, though, has little use for traditional feminine deference, and even less for traditional masculine bravado. She spends her movie tearing through both.

Those other heroines likewise fit traditional ideas of beauty and femininity, clean porcelain faces and perfectly coiffed hair over elegant robes or kimonos (even Crimson Bat’s blindness doesn’t stop her from keeping her wardrobe spotless). Sazen, though, looks the part of a grizzled warrior. She’s missing both an arm and an eye, with a prominent scar to show for it. Her hair starts coiffed, but rarely stays that way, often wild and grungy by the time she’s done with her vicious work. Even her kimono lacks the silken gloss of her contemporaries.

Her rejection of feminine norms goes beyond the physical. She lives in an unusual family unit, with a kindly older villager serving as a quasi-father figure and an orphan child (Yasu) who refers to her as “Sis” as more-or-less a surrogate son. It’s Sazen who’s the clear shot-caller of the family, with no traditional patriarch in sight. Late in the movie she responds to the idea of being someone’s wife with abject revulsion and shock.

She’s also a bit more of a shit-talker than most samurai, male or female, regularly mocking her opponents. She is totally devoid of the reluctance so common to the genre. Zatoichi doesn’t want to fight until he has to, Yojimbo doesn’t want to fight until there’s profit in it. Sazen? She would absolutely fucking love to fight, provocation or profit be damned.

Consider an early scene where she finds out the young woman she’s just saved is being hunted by the yakuza, and they’ve got a bunch of men in a nearby gambling house. Ichi might nod in resolution. Yojimbo might stroke his chin and ponder a plan. Sazen just grins.

Then she heads over to the gambling house, wins a bunch of their money, talks a bunch of shit, and cuts a few misogynistic jerks up with her sword. Because that’s just the kind of gal she is.

The kind I wish they’d made more than one movie about, specifically.

#6: Tokyo Story (1953)

The camera doesn’t move much in Tokyo Story, but with shots like this it doesn’t need to.

This was, admittedly, an eat your vegetables movie for me. It’s a universally beloved classic that I felt I needed to see, but nothing about its subject matter, genre, or cast initially much appealed to me.

Yasujirō Ozu’s Tokyo Story is essentially a story about a pair of elderly folks realizing their kids suck, and mostly not talking about it. In a movie made up almost entirely of scenes of people sitting around and talking, very rarely are they actually saying what they mean. This is especially true in scenes between the adult children and their unwanted parents, but it’s also the case even in more intimate settings, between the two parents reluctant to call their kids shitheads even to each other, and between the children clinging to some thin veneer of anything other than self-interest. It’s not always true, and the moments where it isn’t are the key beats of the film, but they make up relatively little of its runtime.

At a deeper level, it’s about the passage of time, or the way human nature has a short memory when it comes to gratitude, or what exactly constitutes family, or the decay of the family unit, or… this paragraph is as long as you want it to be. Tokyo Story may not be an especially cinematic film by some (wrong) definitions, but it’s certainly a literary one. There are probably more valid interpretations or connotations than there are frames in the movie.

The camera moves only once, I’m told, and I believe it, though I’d be lying if I said I noticed while I was watching. The film hardly lacks for visual flair. Ozu knows he’s making a movie about people sitting on the floor and barely talking to each other, so he makes them impossible to look away from. The shots are meticulously composed and shot, bringing real beauty and energy to mundane settings full of inane conversations.

The children somewhat blend together. They all have their own backstories and temperaments, but their motivations and failings are shared. The exception is Noriko, the widow of one of their siblings. She’s intensely sympathetic, unfailingly kind and generous in the face of grief and poverty, a stark contrast to her more well-to do and selfish in-laws. Setsuko Hara plays her with a sort of feverish warmth, the sort of woman who’d take a bullet to save you stubbing your toe. That she likes herself so much less than we do adds to the effect.

The late scenes with her and the family patriarch (Chishū Ryū) play with an urgency that’s deliberately absent from the rest of the film. So much of the movie is a conflict between obligation and self-interest, while these scenes contain neither; they pit the best natures of the movie’s two most well-intentioned characters at odds. It’s an absolutely fiendish bit of storytelling, as cruel to the audience as to the characters, but you don’t find too many scenes that hit harder, or in more places.

Sometimes vegetables are good for you.

#4 (Tied): The Tale of Zatoichi Continues (1962)

The two most iconic samurai actors of their era square off.

As the series goes on, Zatoichi eventually starts to follow the Bond format where each adventure is more-or-less wholly standalone, but the first few films of the franchise are actually tightly serialized. The second, The Tale of Zatoichi Continues, sees the blind swordsman returning to the site of the first movie one year later in order to keep a promise—and pay respects—to a fallen frenemy. Once there he again encounters Otane (still played perfectly by Masayo Banri), the woman he saved, and ultimately abandoned, a year prior. It’s clear there’s still an intense connection between them, but hectic circumstance and Ichi’s own reticence keep them from doing too much about it.

Also in town are the usual antagonistic yakuza, complicating matters, and a mysterious samurai in their employ who clearly has a deep personal interest in Ichi. This samurai is played by Katsu’s real-life brother, Tomisaburō Wakayama, best known for his own iconic series of samurai films Lone Wolf and Cub. While the first movie saw Ichi reluctant to fight a man with whom he shared a deep mutual admiration, here we see him challenged by someone to whom he has much messier ties. As the movie progresses we learn more about their relationship, and their history, and why Ichi is the way he is…and why he’s so afraid of getting close to Otane.

It’s one of the most emotionally charged Zatoichi movies, and it breaks the mold the series would later cling to of “Zatoichi as underestimated outsider.” In this one, everyone knows who he is, and what he’s done, and Tomisaburō knows even more than that.

It’s also one of the saddest films, and features a uniquely bleak ending. Most Zatoichi movies end with him walking off into the sunset, often on a melancholic or bittersweet note, but more or less triumphant. This one ends very differently. Ichi has not triumphed in any of the ways that would matter to him, and what he does last is not walking away into the sunset at all. Unlike most of his adventures, the consequences of this one will not stay behind as he moves on to future movies, but travel with him, corrosive ghosts of what could have been if only he’d made different choices, or perhaps even the same choices at different times.

No matter how many sunsets he walks into, they’ll never be bright enough to burn this darkness away.

#4 (Tied): Zatoichi The Fugitive (1963)

Masayo Banri steals Zatoichi’s movie out from under him.

After a one movie digression about Zatoichi’s old mentor, the series returns to the Otane arc in the fourth installment, Zatoichi the Fugitive. Here Zatoichi again finds himself with occasion to return to the site of the first and second movies, this time with a hefty price upon his head. Otane is still there, but she’s now married. Worse, she’s married to a ronin who seems very interested in Ichi’s bounty. He also seems to be a bit of a dick, but Ichi knows that’s ultimately none of his business; he’s walked away from Otane twice, he’s got no say in what she does in her life without him.

Otane, for her part, is not as we once knew her. Time and compromise (and Ichi twice abandoning her) have worn away at the optimism and hope that once defined her; she’s now even more cynical and haunted than Ichi. She alludes to great guilt without ever explaining its source, and sometimes seems to view her ronin husband more as the fate she deserves than one she wants. Here she again shames Ichi; he sometimes pays lip service to the idea that doesn’t deserve—or at least can’t maintain—real happiness, but it’s Otane who goes a step further in her self-inflicted penitence and sentences herself not just to a passive absence of joy, but active, self-perpetuating misery.

There are other plotlines, as well, about the mother of a man Ichi kills early on, and about a pair of young star-crossed lovers who might yet have a better shot at happiness than Ichi and Otane. All three stories weave in and out of each other—and in and out of the usual “there’s a bunch of bad yakuza doing bad yakuza stuff to the town” story we get in every Ichi picture—without ever becoming contrived or confusing; this is a masterfully paced film.

It also features the franchise’s best climax* when all those story threads come together, both narratively and in terms of sheer cinematic style. The final two action scenes are among the series’ best, particularly the inevitable duel between Ichi and the ronin. As great as those sequences are, though, they’re given extra heft by the emotional weight the narrative has imbued them with, all courtesy of Otane.

*At least of the eleven I saw in 2021.

Masayo Banri is impossibly good here, making Otane a paradox. She is simultaneously the passionate character we knew before and the eroded cynic she’s become, playing convincingly as both a callous vixen who sees Ichi as little more than a relic of her past that might be exploited, and as a tortured, regretful soul still carrying a torch for the only man who ever treated her like a person instead of property. Which of these two people she actually is, the movie declines to answer definitively. Her actions suggest one, circumstance and dialogue another. It’s not clear she’s even sure herself.

Ichi doesn’t leave the movie knowing the answer. In fact, he leaves knowing he never will.

Across eleven (and I suspect twenty-six) films of his being shot at, stabbed, kicked, burned, betrayed, shunned, mocked, cast-out, and rejected, it’s by far the most we see him hurt, a pulp hero briefly thrust into Shakespearean tragedy.

From here on, the series rarely references much of what came before, but the specter of Otane looms over every relationship Ichi has after, and lends pathos and narrative heft to movies that otherwise might have none.

This one has enough to spare that the subsequent twenty-two never need go without.

#3: The Stairway To The Distant Past (1995)

Maiku Hama goes Technicolor.

The first Maiku Hama movie, The Most Terrible Time in My Life is a great detective story, and the third, The Trap, is triumphantly dreamlike and unhinged. The second film in the trilogy, Stairway to the Distant Past, manages to be both at once, and is the strongest outing of Kaizo Hayashi’s trilogy.

*There are several post-Kaizo Maiku Hama (by then going by Mike Yokohama) adventures, of which I was only able to trick down one, A Forest With No Name. It’s still a good time, but not in the same league as the Hayashi pictures.

The first film was mostly in black-and-white, with color only erupting in an eleventh hour teaser for this one. Here color pervades, and saturates, and brings life… in fact, the absence of color is explicitly tied to death, with a mysterious antagonist known only as The White Man.

**Obviously there’s a racial connotation there as well, and that interpretation works, too, with The White Man as an ephemeral and untouchable exploiter of the Japanese working class.

The White Man is up to no good along the river, and the re-emergence of Hama’s estranged mother forces the hard-luck private eye to investigate. Stairway to the Distant Past takes that setup and gets really, really weird and personal with it, and ends up an underseen modern classic as a result.

The cinematography and set design in all three of the Hayashi-helmed Hama pictures are exemplary, but the crime-ridden riverside that serves as White Man’s territory stands out as one the most surreal and haunting settings I’ve seen in a crime movie. A looking glass nightmare built out of neon and smoke for Hama to descend into. It suffuses the scenes unlucky enough to take place within its borders with the uncomfortable paranoia of a bad trip, with the unshakeable feeling that anything can happen and when it does it’s gonna be weird in the bad way.

He’s supported, too, by two of Japan’s most legendary actors, with Jō Shishido returning as his mentor and Eiji Okada (most famously of Hiroshima Mon Amour and Woman in the Dunes) as The White Man. Shishido leverages his talents to turn exposition into excitement, while Okada creates the series’ scariest—and yet most sympathetic—antagonist. The rest of the cast is game as well—particularly Haruko Wanibuchi as Hama’s long-lost mother—but Okada and Shishido anchor the film, foils despite never sharing a scene, representing the two men Hama might one day grow up to be.

That subtext adds thematic flair to a film already rich with pathos, comedy, action, and tension, and makes for one of the best-looking, strangest, and most satisfying detective movies of the 1990s.

#2: Sanjuro (1962)

Toshiro Mifune is skeptical that he’s as screwed as his captors seem to think. No prize for guessing if he’s right about that.

Yojimbo is back, and this time he wants a nap.

Seriously, that’s the plot. Nine well-intentioned but clueless samurai gather to plot their resistance to a corrupt chamberlain, and interrupt Sanjuro’s (Yojimbo’s new fake name for this outing) naptime. He spends the rest of the movie alternately saving, educating, and insulting them, an unlikely and underslept ally in the face of oppression.

If it sounds like a comedy, that’s because it is. If it also has a reputation as one of the great samurai films, well, it’s that too. Kurosawa was a good enough director to do at least two things well, news at eleven.

Sanjuro is a perfect sequel in that it both understands exactly what was great about the first movie, and how to make that greatness feel fresh and different. In contrast to the Zatoichi series, which tends to put Ichi mostly in the same situation with minor variations, Sanjuro changes the title character’s main obstacle from having too many enemies to having too many allies. Here, he’s responsible for a group of idiots he needs to keep safe, instead of merely a group of idiots he needs to make dead (though there’s still plenty of those, too).

*The two characters eventually cross paths and swords in Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo, but I haven’t seen that one yet; it’s the twentieth installment in Ichi’s series.

His interactions with the heroic idiots are responsible for a lot of the laughs, not just in his casual disrespect towards them, but in the contrast between their noble-but-stupid idealism and his not-pretty-but-damn-sure-effective pragmatism. The same is true of the drama. While the villains have their moments of cleverness, for the most part the heroes get into trouble when the idiots don’t listen to Sanjuro and bumble into making the situation worse. Sanjuro is far from blameless there, as his abrasive temperament and apparent self-interest don’t make him an easy man for good people to trust.

That’s a pretty good joke itself, if a little more meta than we’re used to in our swordfight movies. We only know who Yojimbo/Sanjuro is in the first place because he’s the kind of good guy it’s easy for bad guys to believe in. Turns out that feature can also be a bug.

The action is predictably excellent, and the pace is crisp. Like Yojimbo before it, the central pleasure is in Mifune’s performance, and it’s not hard to imagine him making a dozen more of these if that’s what he (and Kurosawa) had wanted to do. There’s nearly infinite mileage in the idea of a samurai who’s greatest weapon is his wit, and there’s no better actor for the part.

Of course, having made this one and Yojimbo, there wasn’t much need for more, either. They’re so good, and so dense in their cleverness and excitement, you could just rewatch them both every year and have just as much fun as if there were new installments.

#1: Zero Focus (1961)

Ineko Arima and Hizuru Takachiho trade secrets and glares.

A woman’s new husband goes missing. She goes looking for him. As noir setups go, that’s a pretty basic one. It’s about the only part of Zero Focus you can call basic.

The movie has little use for traditional three act structure; instead, you get about an hour of amateur sleuth investigation followed by a nearly forty-minute climactic conversation that still feels like it’s over far too soon. It’s an inspired riff on the classic detective parlor summation scene. In place of the parlor, we have a striking craggy cliffside. In place of a professional sleuth coolly enumerating the facts of a case he’s been brought int to solve, we have a wounded woman slinging venom in the direction of those she blames. There are other, more significant variations on the trope as well—her confidence, for instance, may be less absolute (or less earned) than Poirot or Blanc’s—but to say too much is to say too much.

Zero Focus is a difficult movie to talk about without spoiling. The plot appears simple at the outset but rapidly becomes elaborate. Every twist or revelation opens up alternate, mutually exclusive theories that our heroine must choose between or track down. Nearly every character knows more than they’re letting on… or they think they do, and actually know much less.

In broadest strokes, Zero Focus is the story of three women. Teiko (Yoshiko Kugai), the wife of the missing man and budding amateur sleuth. Hisako (Ineko Arima), another woman missing an absent husband, though hers at least was considerate enough to leave a suicide note. And then there’s Sachiko (Hizuru Takachiho), a happily married older woman of some distinction who might know something about one of the missing husbands, or both, or neither.

Each of these women has their own theories about what has happened, and why, and those theories evolve as the movie progresses. They engage with the world around them differently. Teiko is deferential but dogged, a middle-class woman on a mission, but also a stranger in a strange, unfamiliar land, who knows she must tread carefully. Hisako, meanwhile, is despair incarnate, defined by the loss of the only thing she had that counted. Sachiko sticks out, initially, upper class and confident with a present, unmysterious husband. She would not be in the movie if that was all there was to her.

Their interactions are not what you’d expect. The resolutions to every mystery aren’t, either, but they all follow Chandler’s Law: The solution, once revealed, must seem to have been inevitable. They are unraveled not only by canny detective work but by the sharpest edges of the human psyche; hope, despair, and guilt do at least as much crime-solving as deduction and evidence do.

If it were only a great mystery, it would be on this list. But it is also a beautiful one, set in a remote peninsula made of snow and crags that would work as well for a gothic horror, and shot with an eye for wonder and fear. It, too, has more than murder on its mind; the three women come from different social strata, and it matters. It matters, too, that they are women in a society where that often works against them, though each finds her own sort of solution to that particular problem.

It is, last and most importantly, a character story. Consider a scene on a bridge, where one character arrives intending to solve a mystery and another arrives intending to cover it up. The scene at first pretends it will play out as we expect—someone is going over that bridge. What happens instead is so ingenious and unexpected as to redefine the whole film in a single scene, and yet completely logical and inevitable given the characters in it.

It’d be the best scene in almost any other movie, and it might still be the best scene in this one. But the highest compliment I can pay to Zero Focus is that it has an awful lot of competition.

APPENDIX: THE WHOLE DAMN LIST

Here’s all 50, for the curious. Arranged by star rating. Anything over 3.5 is probably worth your time, and anything over 4 is really worth your time.

★★★★★

Perfect Movie

Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion (1972)

★★★★³/⁴

Transcendent

Lady Snowblood (1973), Zero Focus (1961), Sanjuro (1962), Yojimbo (1961)

★★★★¹/²

Must See

The Tale of Zatoichi (1962), The Stairway to the Distant Past (1995), Zatoichi the Fugitive (1963), The Tale of Zatoichi Continues (1962)

★★★★¹/⁴

Excellent

Tokyo Story (1953)

★★★★

Superb

Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold (1964), Lefty Fencer (1969), Velvet Hustler (1967), Okatsu: The Female Demon (1968), Sex and Fury (1973) Crimson Bat, the Blind Swordswoman (1969), Sympathy for the Underdog (1971)

★★★³/⁴

Great

The Most Terrible Time in My Life (1994), Wandering Ginza Butterfly: She-Cat Gambler (1972), Red Peony Gambler (1968), Zatoichi's Flashing Sword (1964), Zatoichi and the Doomed Man (1965) Blood for Blood (1971), Cyborg She (2008), Stakeout (1958), Black Sun (1964) Cat Girls Gamblers: Abandoned Fangs of Triumph (1966), Cat Girls Gamblers (1965)

★★★¹/²

Very Good

Cat Girls Gamblers: Naked Flesh Paid Into the Pot (1965), Zatoichi's Revenge (1965), Fight, Zatoichi, Fight! (1964), The Trap (1996), Okatsu the Fugitive (1969), The Dragon of Macao (1965), New Tale of Zatoichi (1963), Adventures of Zatoichi (1964), The World of Kanako (2014), Quick-draw Okatsu (1969)

★★★¹/⁴

Good

Zatoichi On The Road (1963), Red Peony Gambler: Flower Cards Game (1969), Cat's Eye (1997), A Forest With No Name (2002), Intimidation (1960)

★★★

Fun But There’s Some Flaws

Red Peony Gambler: Gambler's Obligation (1968), Colors of Wind (2017), Melody of Rebellion (1970)

★★³/⁴

Flawed But There’s Some Fun

Outlaw: Goro the Assassin (1968), Rica (1972), Outlaw: Heartless (1968)

★★

Just Bad

Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams (1970)